National Review: Amid a Revival of Anti-Monopoly Sentiment, a New Book Traces Its History

American history began with conflict over monopolies. English colonial charters were monopolies on settlement in wide swathes of territory here. The Boston Tea Party was caused, in part, by resentment at the British East India Company’s monopoly on tea. After independence, monopolies abated for a time, as the country was large and diverse enough to make it difficult for one company to dominate an industry. With the growth of rail and telegraph in the second half of the 19th century, though, distances were less of an issue, and monopoly power became a concern once more. So Republicans and Democrats joined together to pass the Sherman Act of 1890, which allowed them to tell voters that they’d stood up to powerful corporations.

Matt Stoller of the Open Markets Institute picks up the story from there in his new Goliath: The 100-Year War Between Monopoly Power and Populism, which tells the tale of the American anti-monopoly movement in 600 well-researched pages that show a deep dedication to the topic.

As with many issues that have emerged (or re-emerged) over the past few years, it is not easy to decide whether anti-monopoly sentiment “belongs” to the Left or the Right. Stoller’s narrative begins as a typically le”

Matt Stoller of the Open Markets Institute picks up the story from there in his new Goliath: The 100-Year War Between Monopoly Power and Populism, which tells the tale of the American anti-monopoly movement in 600 well-researched pages that show a deep dedication to the topic.

As with many issues that have emerged (or re-emerged) over the past few years, it is not easy to decide whether anti-monopoly sentiment “belongs” to the Left or the Right. Stoller’s narrative begins as a typically le”

Matt Stoller of the Open Markets Institute picks up the story from there in his new Goliath: The 100-Year War Between Monopoly Power and Populism, which tells the tale of the American anti-monopoly movement in 600 well-researched pages that show a deep dedication to the topic.

As with many issues that have emerged (or re-emerged) over the past few years, it is not easy to decide whether anti-monopoly sentiment “belongs” to the Left or the Right. Stoller’s narrative begins as a typically le”

Matt Stoller of the Open Markets Institute picks up the story from there in his new Goliath: The 100-Year War Between Monopoly Power and Populism, which tells the tale of the American anti-monopoly movement in 600 well-researched pages that show a deep dedication to the topic.

As with many issues that have emerged (or re-emerged) over the past few years, it is not easy to decide whether anti-monopoly sentiment “belongs” to the Left or the Right. Stoller’s narrative begins as a typically le”

Matt Stoller of the Open Markets Institute picks up the story from there in his new Goliath: The 100-Year War Between Monopoly Power and Populism, which tells the tale of the American anti-monopoly movement in 600 well-researched pages that show a deep dedication to the topic.

As with many issues that have emerged (or re-emerged) over the past few years, it is not easy to decide whether anti-monopoly sentiment “belongs” to the Left or the Right. Stoller’s narrative begins as a typically left-leaning history of the early 20th century, but as the tale unfolds one begins to see elements that fit more neatly with some strains of modern conservative thought. Modern conservatives are known for wanting a small government, centered on local concerns and responsive to the people, yet are also often quite comfortable with the consolidation of big nationwide businesses that dominate their fields. Modern progressives, meanwhile, are favorably disposed toward a centralized government that ignores local variation, but they hate a business that does the same.

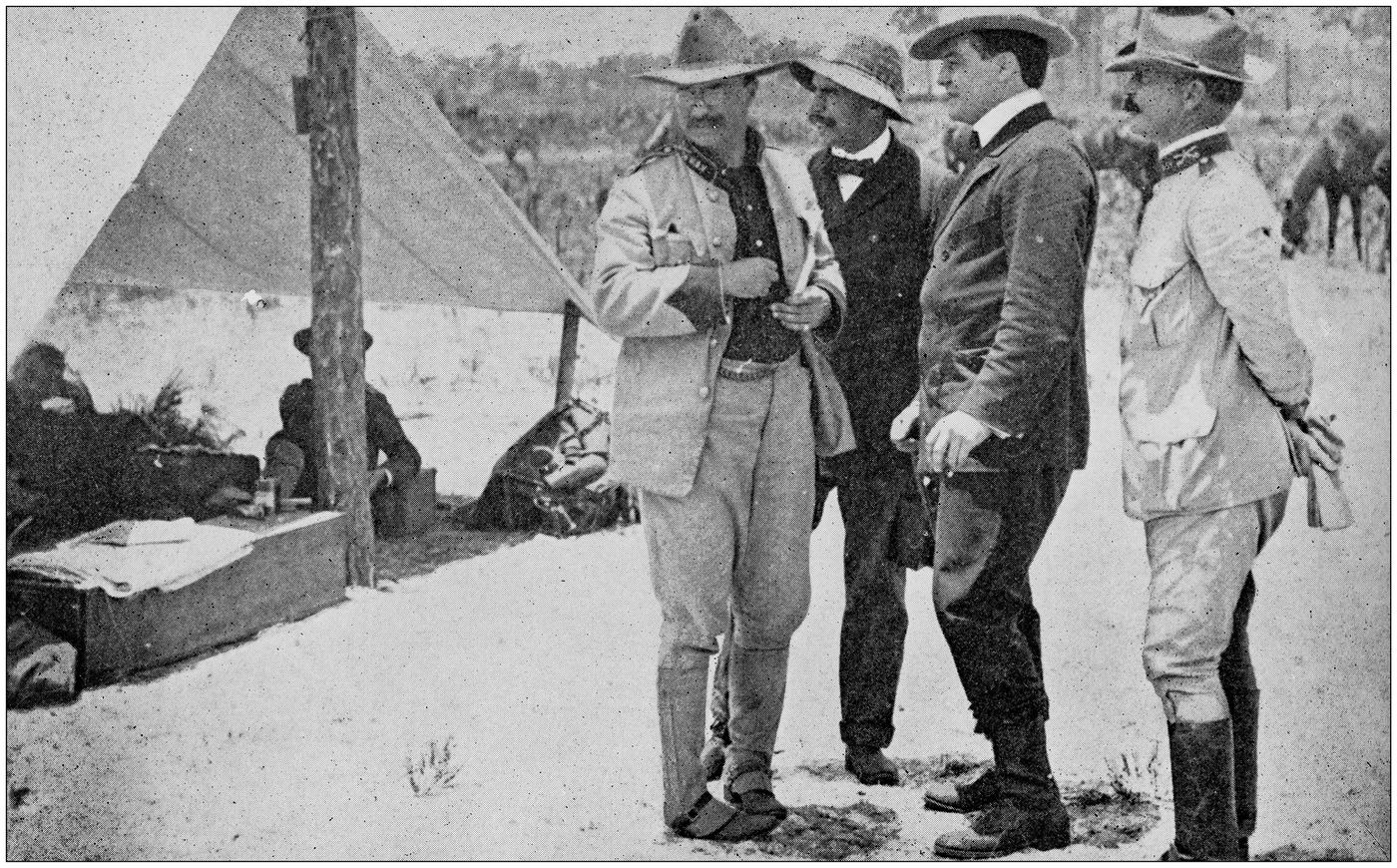

The contrast between our politics and those of a century earlier is dramatic. As Stoller tells us, both parties in 1912 claimed the mantle of progressivism, as did, obviously, Theodore Roosevelt’s Progressive party. The three-way election that year featured Roosevelt and Woodrow Wilson, both of whom claimed to be progressive, and William Howard Taft, who showed some considerable progressive leanings himself.

The differences between them were nonetheless considerable, especially as concerned the issue of anti-trust enforcement. After busting one major trust, Roosevelt tried to make peace with big business. He saw the government’s role as that of organizer: As long as the products being produced were safe for consumers, he was indifferent to the size of the company producing them. If anything, he preferred businesses to be large; it is easier, after all, to regulate and organize a few companies than it is to corral hundreds of independent operators. Roosevelt’s progressivism was, in short, one of big businesses and a government big enough to keep them in line.

Wilson, on the other hand, ran as a small-government progressive. That sounds like an oxymoron to modern ears, but Wilson’s theories, influenced by future Supreme Court justice Louis Brandeis, were in many ways the opposite of Roosevelt’s. He wanted to keep the government small, which meant that businesses had to be small, as well, lest they overpower the state. His New Freedom program would have used the anti-trust laws more aggressively and maintained a smaller government to act more as a policeman to business than an organizer.