The New York Times: The Supreme Court Case That Could Give Tech Giants More Power

Big tech platforms — Amazon, Facebook, Google — control a large and growing share of our commerce and communications, and the scope and degree of their dominance poses real hazards. A bipartisan consensus has formed around this idea. Senator Elizabeth Warren has charged tech giants with using their heft to “snuff out competition,” and even Senator Ted Cruz — usually a foe of government regulation — recently warned of their “unprecedented” size and power. While the potential tools for redressing the harms vary, a growing chorus is calling for the use of antitrust law.

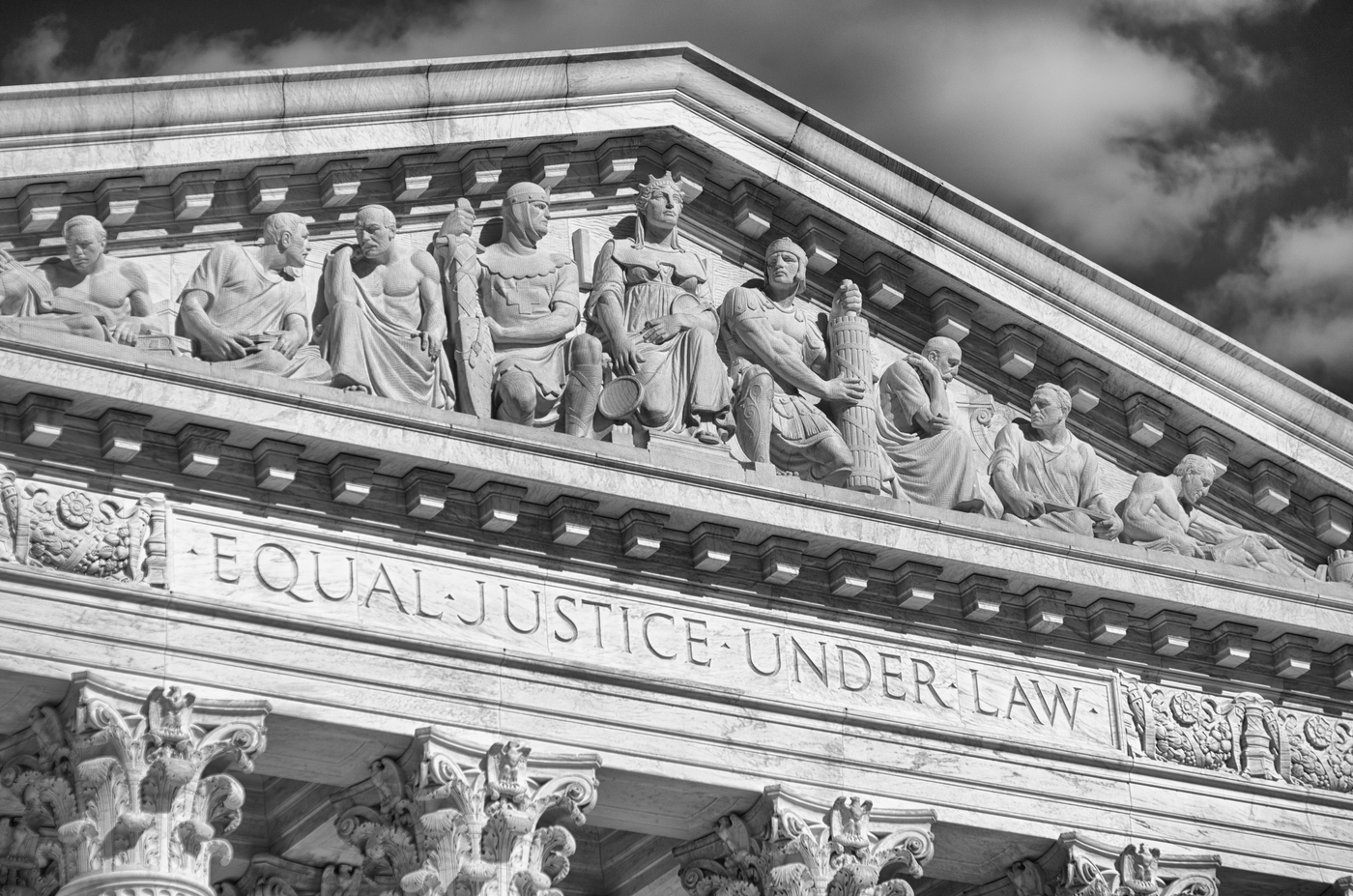

But the decision in a case currently before the Supreme Court could block off that path, by effectively shielding big tech platforms from serious antitrust scrutiny. On Monday the Court heard Ohio v. American Express, a case centering on a technical but critical question about how to analyze harmful conduct by firms that serve multiple groups of users. Though the case concerns the credit card industry, it could have sweeping ramifications for the way in which antitrust law gets applied generally, especially with regards to the tech giants.

The case was first brought by the Justice Department against American Express, Visa, and Mastercard for imposing anticompetitive restrictions on merchants. The credit card industry is a classic case of oligopoly. Despite involving millions of merchants and hundreds of millions of cardholders, the credit card business is controlled by four firms.Merchants who need payment networks lack any real bargaining power and have been stuck paying high rates to the oligopoly — steeper costs that ultimately get passed on to consumers.

As one might expect, the credit card companies use their power to block competition. American Express did this by imposing conditions on retailers that accept Amex cards. Retailers were told they could not ask their own customers to use, say, a Discover card, over an American Express card, even if Discover would be a cheaper option. Discover could provide a merchant like The Home Depot better terms than American Express — but, because of American Express’s restrictions, The Home Depot had no way of reflecting Discover’s lower rates to cardholders, thereby keeping Discover’s competitive advantage from translating into greater market share. This meant card networks had no reason to compete when serving merchants, keeping prices high.

The district court ruled that American Express’s “anti-steering” provisions stifled price competition and violated the antitrust laws (Mastercard and Visa settled with the government before trial). But when American Express appealed, the Second Circuit reversed, relying on a new concept to create a special set of rules. The concept is that players in “two-sided” markets are unique because they serve different sets of customers in distinct but related markets, effectively facilitating transactions. American Express, for example, charges both merchants who accept its cards and consumers who use them. Using this concept, the Second Circuit held that the government would have to show that any price increases for merchants also harmed cardholders, or at least didn’t benefit them. In effect, the court introduced a dramatically new rule, making it much more difficult to win important antitrust cases and to stop anticompetitive behavior.