Washington Monthly - A Free Market Won’t Self-Correct the Disinformation Problem

In a Washington Monthly piece co-authored with Eric Cortellessa, Philip Longman of Open Markets Institute urges Congress to address disinformation by enforcing policies that protect our free and competitive media markets.

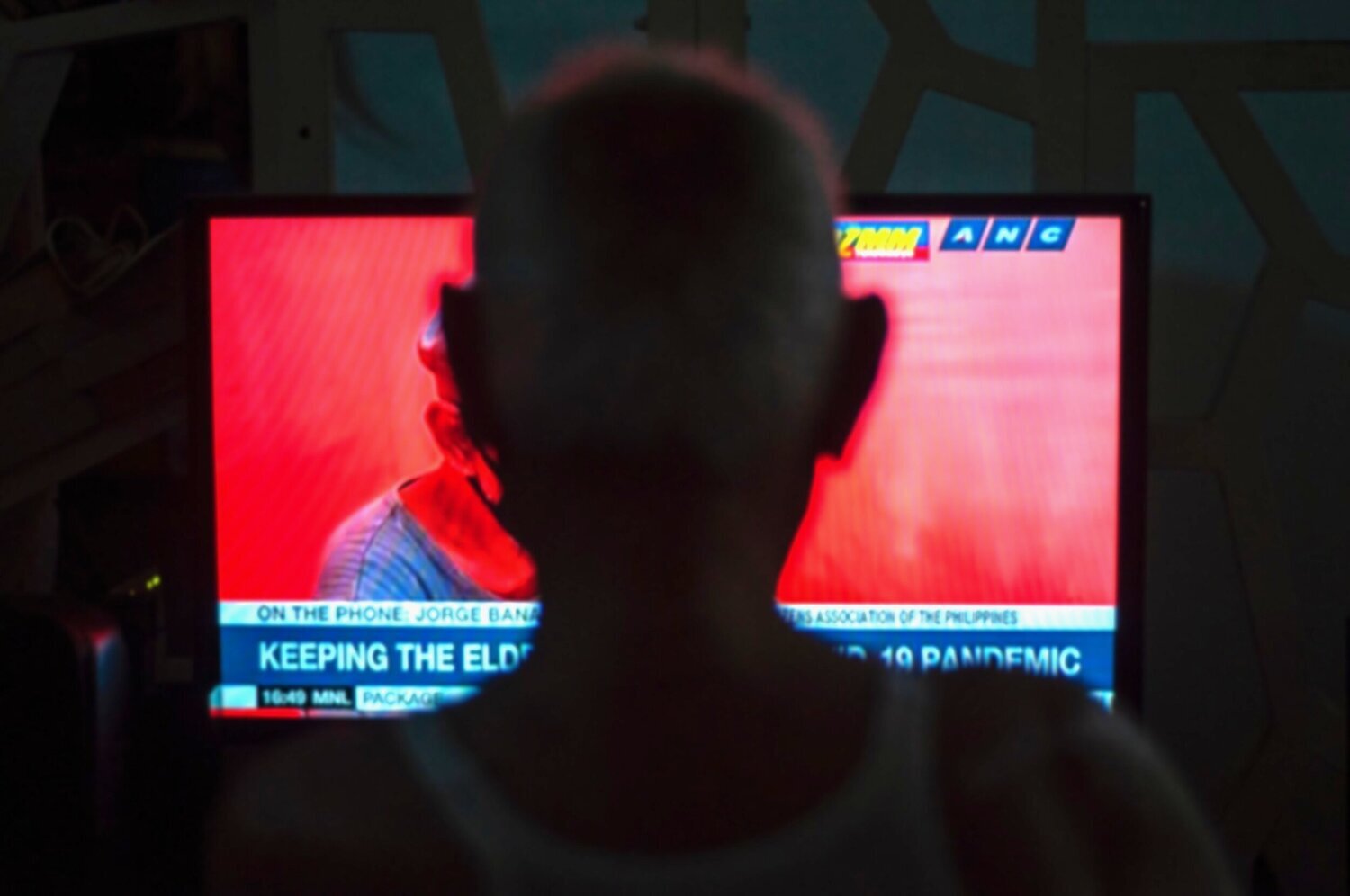

Against a backdrop of mounting concern over the role Fox News, One America News Network, Newsmax, and other conservative broadcasters play in disseminating disinformation to tens of millions of Americans, the House Energy and Commerce Committee held a hearing on Wednesday to shed light on the issue. Sadly, the root causes of the problem remained mostly in the dark.

With one exception, familiar witnesses made familiar talking points. Former CNN host Soledad O’Brien stated that “Congress can’t, and shouldn’t, regulate journalism,” but rather journalism should regulate itself. “Balance does not mean giving a voice to liars,” she told the lawmakers. George Washington University law professor, Jonathan Turley, a favorite of the Republicans, also rejected any role for government in combating media organizations that spread misinformation, repeating the trope that “free speech is the greatest protection against bad speech.”

Underlying these formulations is a conviction, shared by many people across the political spectrum, that the problem of disinformation can be self-correcting if only the government will refrain from censorship and let competition in the “marketplace of ideas” work its magic. It’s an old and noble idea tracing back to the Enlightenment and was central to the Founders’ notion of how a democracy can root out error and act on truth. But to work in practice, it requires, as the Founders also well knew, that the government must not allow the marketplace of ideas to become cornered.

Up until the 1980s, the federal government played a very active role in structuring media markets, particularly in the realm of broadcasting, to ensure that they remained open, competitive, and not monopolized by any one point of view. Still, only one of the witnesses at the hearing, Emily Bell of the Columbia Journalism School, even alluded to the dire consequences of America having almost entirely abandoned these policies.

The example she cited was the Fairness Doctrine. Enacted by the Federal Communications Commission in 1949, the measure expanded pre-existing requirements on broadcasters that they offer a diversity of news sources and opinions. As media historian Victor Pickard has written, its purpose was to uphold Americans’ First Amendment right to not have their own viewpoints and that of their fellow citizens suppressed by giant media companies. But the FCC repealed this doctrine in 1985. Predictably, a new kind of hyper-partisan—and increasingly fact-free news programing—started polluting the airwaves shortly thereafter. If not for the Fairness Doctrine’s repeal, it would have been illegal for broadcasters to let Rush Limbaugh and like-minded ranting ditto heads monopolize their programming.

This policy error is just one of many examples of how a triumph of corporate libertarian ideology has undermined the open marketplace of ideas. As Daniel Hanley has previously detailed for the Monthly, between the 1930s and the 1970s, the FCC exercised its vast statutory authority to contain the growth of media monopolies and prevent them from abusing their power. It did so through such measures as stopping or breaking up big media mergers; by enacting rules that favored local ownership of television and radio stations; and by insuring that station ownership was not limited to just rich white men. The FCC also assured an open marketplace of ideas by preventing cross-ownership of newspapers and broadcasts stations, and, perhaps most importantly, enforcing strict structural separations between networks, broadcasters, and studio production companies (a.k.a., content producers).

Read the full article on Washington Monthly here.